Ritual and Shamanism

Research Projects and Fieldwork

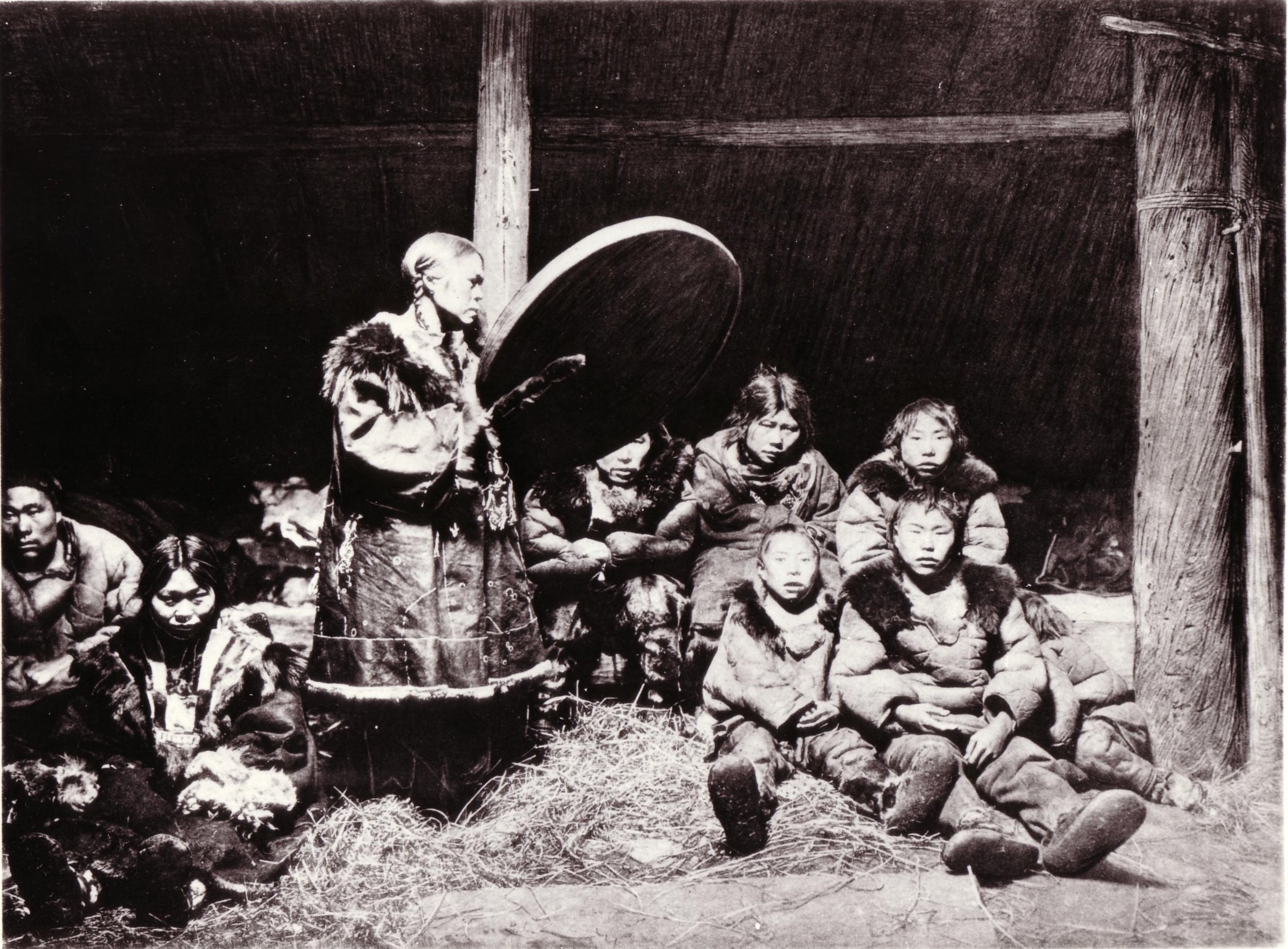

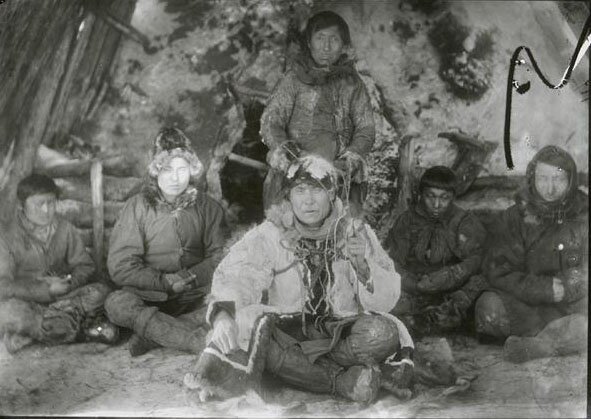

Archival, Circumpolar North

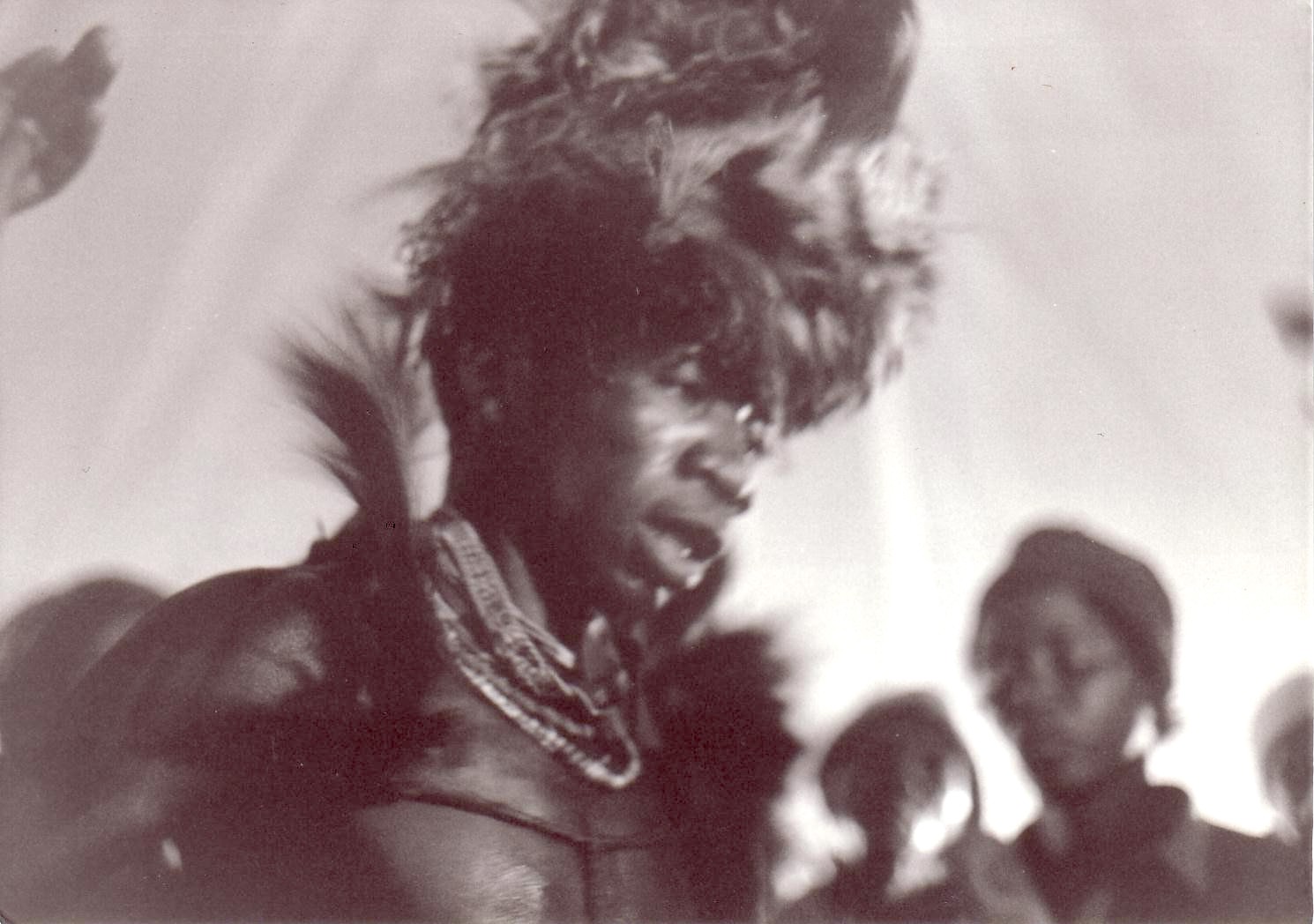

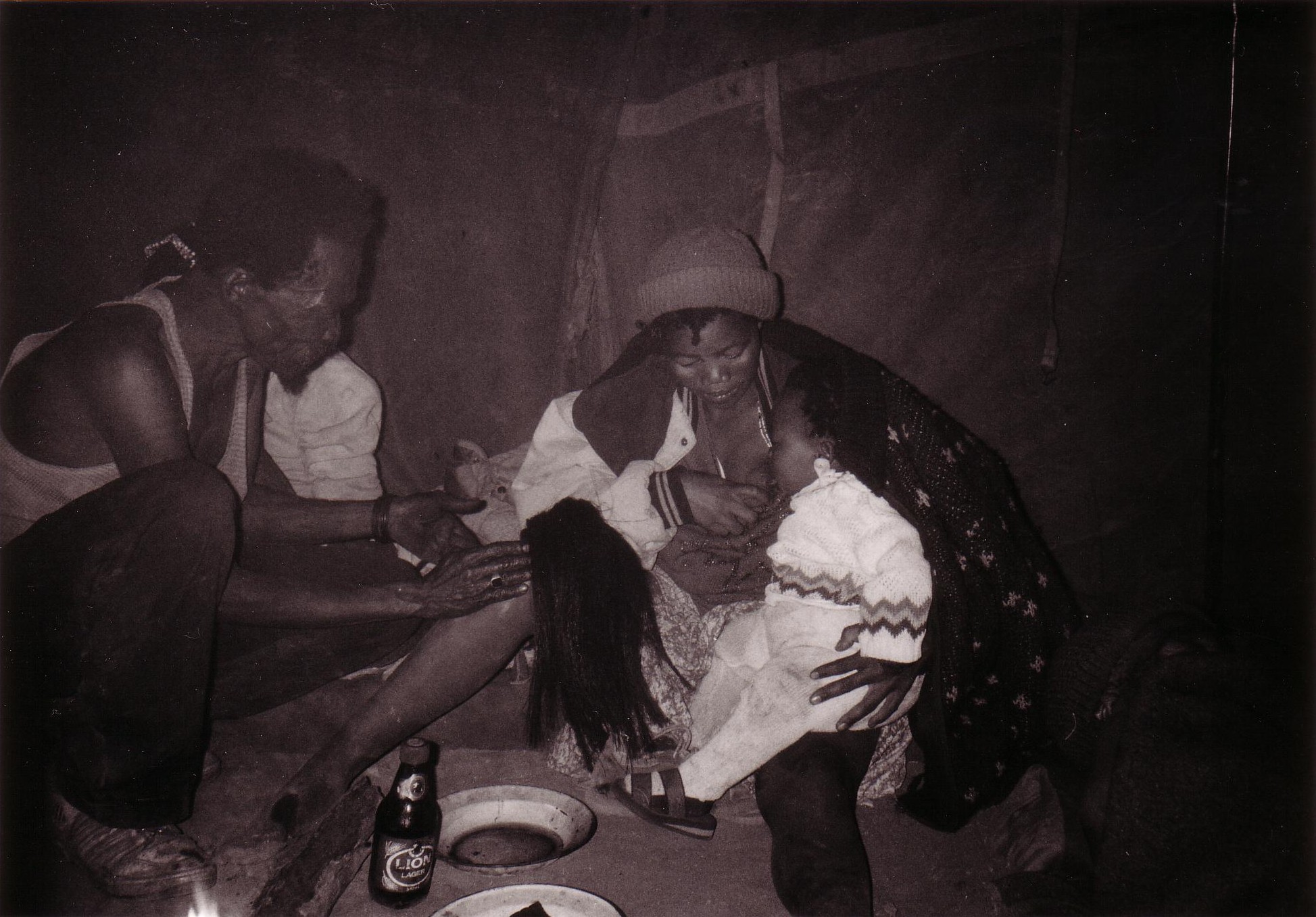

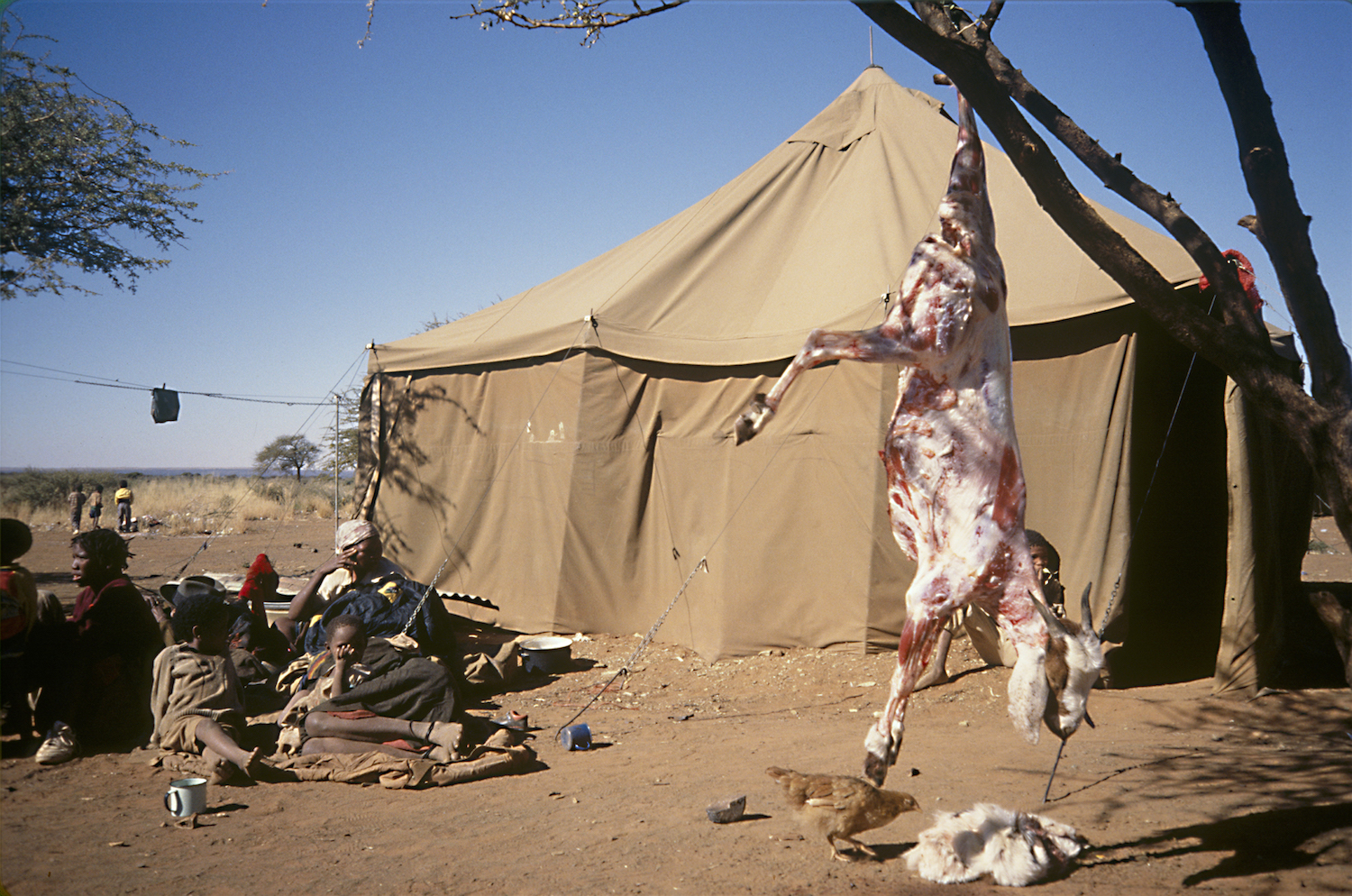

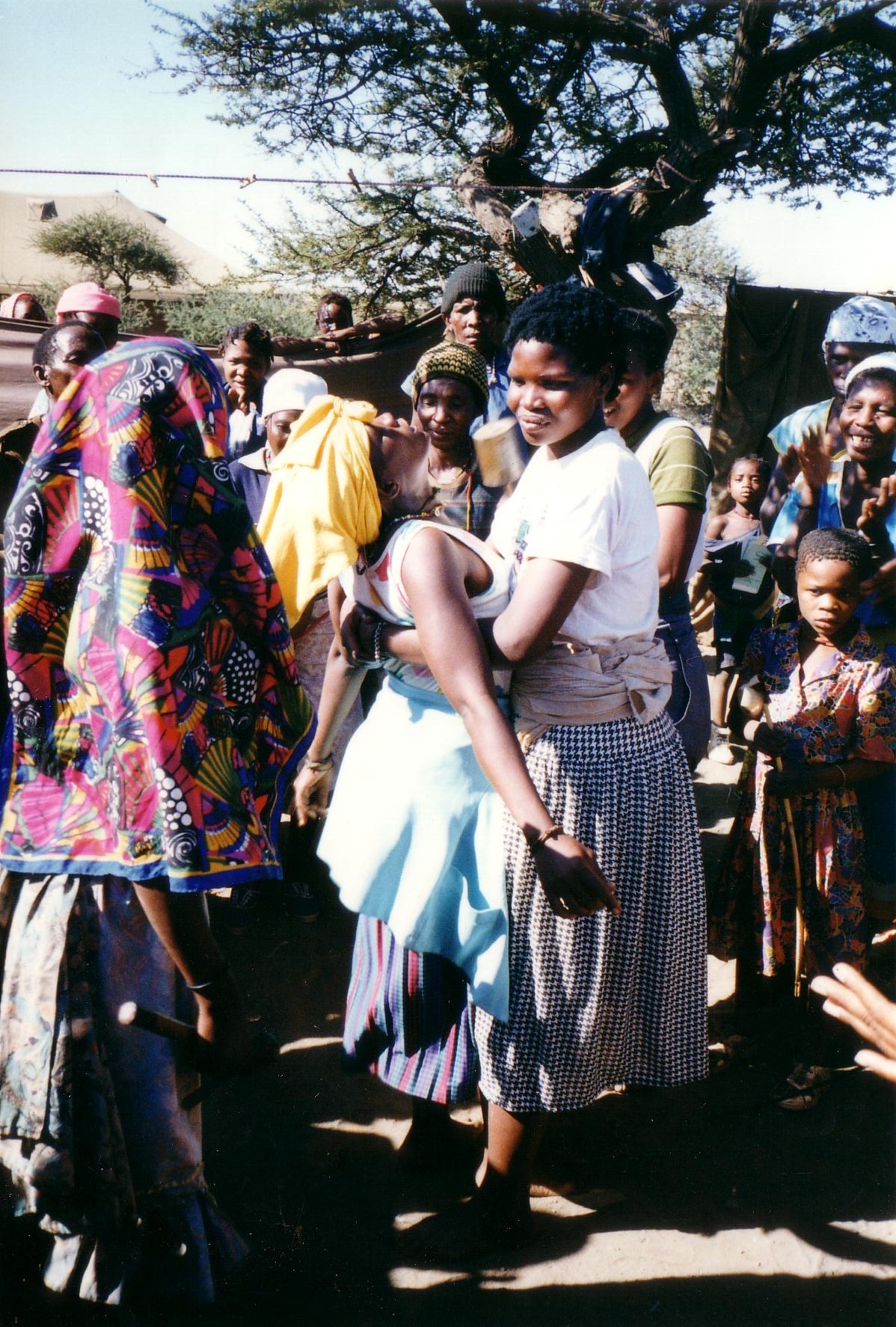

!Xuu and Khwe Bushmen, Kalahari Desert

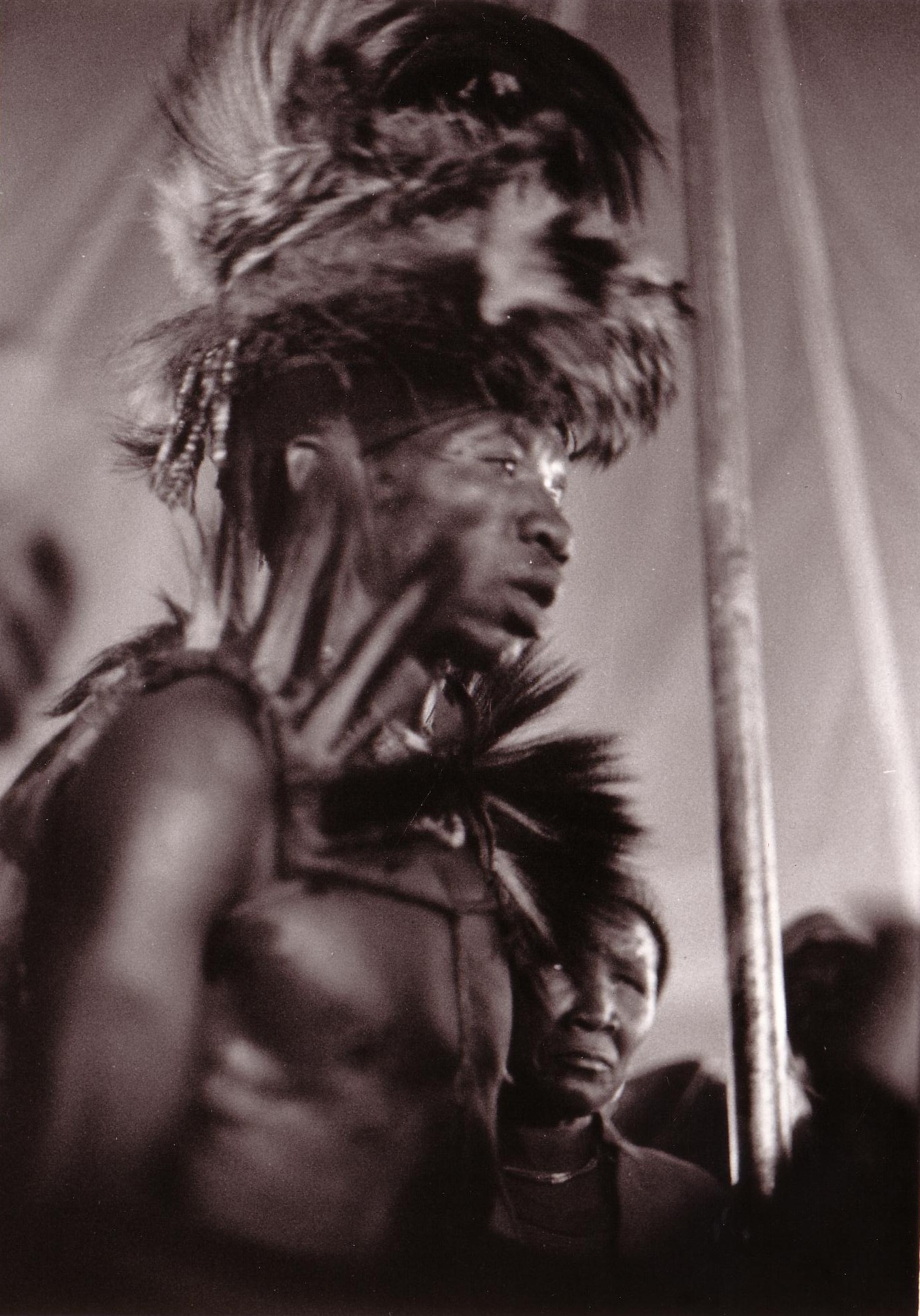

Several sets of rattles combined with the polyrhythmic drumming and three levels of women clapping. Machai led the song with others singing chorus. A few women added high-pitched birdcalls. Machai was shaking his shoulders and head and soon others joined the dancing, shaking with a shuffle step across the floor. The dance and song cycled, weaving the room into another space, one outside my normal sense of time and reality. Soon most of those in the trailer were shaking at the shoulders and hips to create “heat.” Silenga, a small, older woman, also wore a beaded headpiece. Her eyes were closed and her face relaxed--she was entering an altered state of consciousness. The dance and song had many spontaneous swells of emotion and energy that pleased the group. The dance took them to some other place deep within their cultural identity, a place where they were happy.

from N!ngongiao: People Come Out of Here. Making a New Story with the !Xuu and Khwe Bushmen

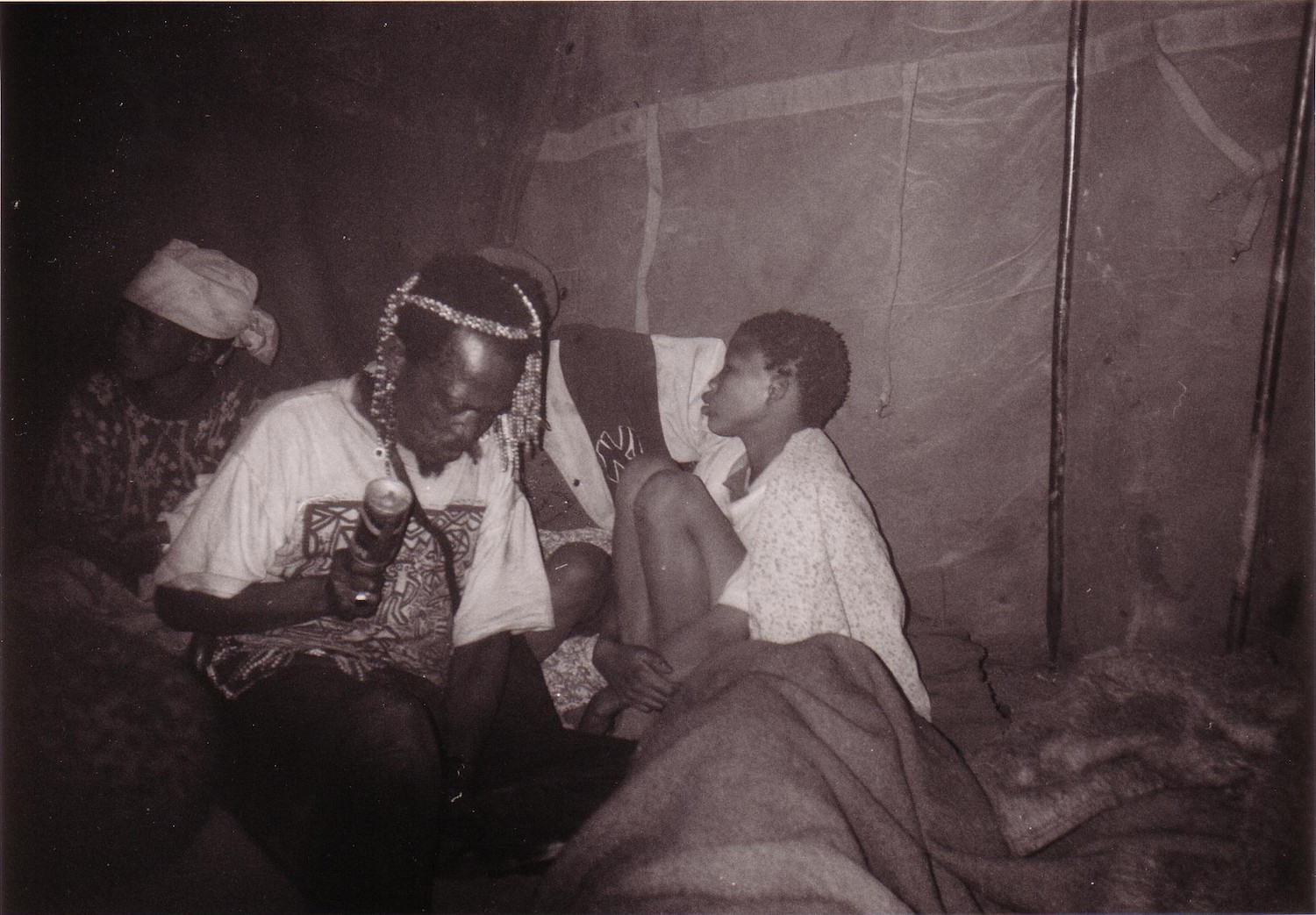

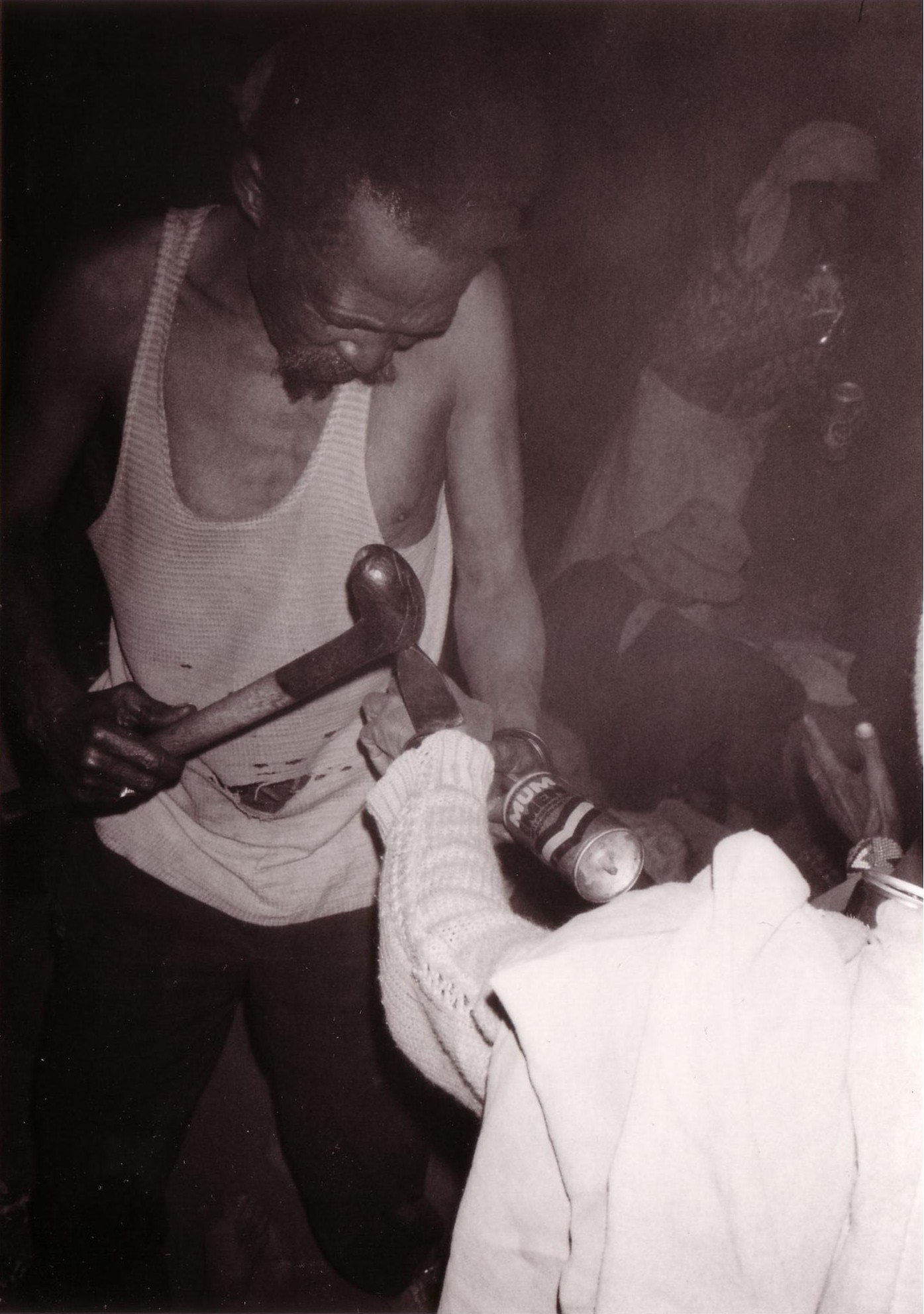

What do you do with the sickness?

Sometimes I see the sickness as a black stone, and it is very heavy. Everyone sees it once I pull it out. Then I throw it into the fire, and only I can see it shooting away. It looks like a glowing beam of red light flying away. I can see the sickness with my eyes. By the time the sun comes up, l can see the disease around the person's body, moving around like a breath, like steam.

When the person is healed, that person will get up and eat something, go to work, or walk. I put a bit of medicine on the piece of cloth (a pendant) I wear, and then I use it to wipe the medicine on either side of the person's throat for protection.

an excerpt from Today We Sing,

Korean Mudang

As she spoke Mrs. Jong became younger, almost child-like, her face and shoulders moving with dance rhythms only she heard; occasionally she shuddered with some unseen touch. Her vocal patterns fell into the patterns of a chant as we all watched with curiosity, fascination, and anticipation. Chang Chong-il slept contentedly in her grandmother’s lap. Mrs. Jong’s two lady friends nodded with affirmation, swaying and rocking as if they, too, felt the spirits near. Mrs. Jong’s low singing increased in volume to encourage the spirits to enter the room. Her body shuttered as if suddenly possessed. Concerned, her son and daughter came near and watched their mother speak in the dialect of the spirits.

Then Mrs. Jong stopped as suddenly as she had started, looking at us as if someone just startled into wakefulness, wondering why people were staring at her.

She lit a cigarette, “The spirits like to smoke,” she laughed. “The spirits are good to me, they protect me when I am on the knives. So I smoke to please them.”

from A World Away

Zulu

South Africa

Sakha Republic

“One day when I was wandering in the fields, I began to sing and could not stop. I was young, a boy and not a man. Before that day, I had many feelings, dreams, and nightmares. I heard and saw things that were not there. I wandered lost in the forest and sleep to awake, where I was or my name. I escaped for many days to the taiga; I became weak in mind and body without food or sleep. I know now the spirits were preparing me. One day I began to sing and could not stop. I sang for many hours, and my father put me in a skin tent to sing for many days. The spirits would not let me sleep, eat, or drink. This is how the spirits taught me how to call them.””

When we first arrived I had walked the entire perimeter of Izbekhov’s compound, thinking I had seen everything. I hadn’t, and was caught by surprise when Izbekhov led us into a grove containing his magnificent shaman's tree. The tree was stripped of its bark, carved and without leaves, its upper branches reaching like fingers on a hand reaching skyward as if alien antenna. Affixed to its central pole was a milchmare skull. At its base, to about seven feet off the ground, were several small, crudely carved totem spirits, representing ancestors, helping, and tutelary spirits. In the cracks, grooves and grain of the tree were stuffed coins and folded currency, offerings to the spirits. Extending from the tree on weathered diagonal log, were perched, in line as if ready to take flight, nine bird carvings. Each carving was unique, each a different kind of bird and a different size. Each bird carving, going from largest to smallest represented another level of his advancement as a shaman. They signified, and were what remained, of Izbekhov’s great Shamanic powers. Through his frailty he strained to tell us, in detail, about each of the bird figures. He said it was important we knew.

from Diary of Siberia

Sakha shaman’s drum

Archival, Sakha Shamanism

Sakha shaman’s coat, archival